by E. Wyn James

‘One of the best guarded secrets of the Island of Britain’

is how a leading authority on Christian spirituality, Canon A.

M. Allchin, once described the hymns of Ann Griffiths, a tenant

farmer’s daughter from mid-Wales who died in relative obscurity

in 1805, aged 29, leaving just over 70 stanzas in the Welsh language

which contain some of the great Christian poetry of Europe.

Ann’s hymns have long been regarded as one of the highlights

of Welsh literature, and since the mid-nineteenth century she

herself has become a prominent icon in Welsh-speaking Wales. Reams

have been written about her life and work. She has been the subject

of novels, dramas, films and numerous poems. Latterly, through

the efforts of Canon Allchin and others, she is becoming increasingly

well-known to students of hymnology and spirituality outside Wales

– not least following the inclusion of an English translation

of one of her hymns in the service of enthronement of Dr Rowan

Williams as Archbishop of Canterbury in February 2003.

‘Despite the limitations of her work,’ says Canon

Allchin, ‘her stature is to be measured against the great

and unquestioned figures of the Church’s history.’

Such a claim contrasts starkly with her insignificance during

her own lifetime, except within a fairly close circle of friends

and acquaintances.

|

| Dolwar

Fach

(Illustration: R. Brian Higham)

The present house was built after Ann Griffiths's day. The old farmhouse was a long, thatched, single-storey building. |

The main events in her life can be summarised in a few sentences.

She was born ‘Ann Thomas’ in the spring of 1776 on

a farm called Dolwar Fach in the parish of Llanfihangel-yng-Ngwynfa,

near the market town of Llanfyllin in Montgomeryshire in north-east

Wales. Technically, the part of Llanfihangel where she was born

belonged to the parish of Llanfechain, some eight miles east;

however, a long-standing arrangement meant that the inhabitants

of that area were counted for all intents and purposes as parishioners

of Llanfihangel-yng-Ngwynfa, and it was in Llanfihangel parish

church that Ann was christened on 21 April 1776. She became mistress

of Dolwar Fach at 17 years of age, following the death of her

mother in January 1794. Her father died ten years later, in February

1804, leaving her and her brother John to run the farm. In October

1804 she married a young man of the same age from the next parish,

Thomas Griffiths – and that is why she is known as ‘Ann

Griffiths’, despite the fact that it was as ‘Nansi

Thomas’ that she would have been known by all and sundry

for most of her life. On their marriage, Thomas came to join Ann

and her brother at Dolwar Fach. Then, ten months later, in August

1805, Ann died aged 29, following the birth of a baby daughter,

Elizabeth (who was born on 13 July and buried on 31 July, two

weeks before her mother).

Ann Griffiths lived throughout her short life in the same farmhouse

in northern Montgomeryshire, and was buried within a stone’s

throw of that farmhouse, at Llanfihangel-yng-Ngwynfa parish church,

where she had been christened and married. However, this brief

outline does scant justice to the richness and fullness of her

life, for as Canon Allchin has said on more than one occasion,

it would not be inappropriate to apply to the brief compass and

narrow confines of Ann’s life, a couplet from a poem by

that great Welsh mystic poet of the twentieth century, Waldo Williams

(1904–71):

Beth yw byw? Cael neuadd fawr

Rhwng cyfyng furiau.

[What is living? Having a great hall

Between narrow walls.]

An age of transformation

Ann’s lifetime, the last quarter of the eighteenth century,

was an age of great change in many spheres – in agriculture,

industry, politics, culture and religion. It was an age of great

awakenings – the age of the French Revolution and the Methodist

Revival. Ann was 13 years old at the time of the French Revolution.

That was followed almost immediately by an extended period of

warfare between Britain and France. Indeed, Britain and France

were at war for almost the whole of Ann’s adult life. One

of the keenest supporters of the French Revolution and its radical

principles was William Jones (1726–95), who lived in Llangadfan,

in fairly close proximity to Ann Griffiths. He was an ardent Welshman

who was at one time intent on establishing a Welsh-speaking colony

in America. He was such a fervent supporter of radical principles

that his letters were intercepted by Government spies. Ann Griffiths

moved in less radical circles politically, but the war with France

deeply concerned her and, after joining the Calvinistic Methodists,

she would regularly attend the prayer meetings held on Wednesday

mornings specifically to pray about the war.

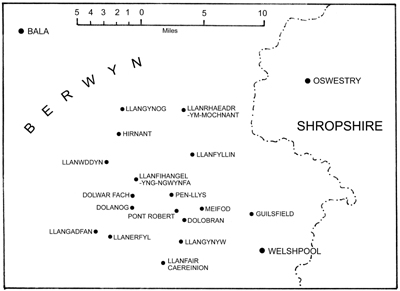

|

Map of Wales

showing

Dolwar Fach

(Christine James) |

As Dr Enid Roberts has emphasised, Llanfihangel-yng-Ngwynfa was

not as remote as one might imagine in Ann’s day. By that

time coaches which ran regularly along routes from London to Holyhead,

from Chester to Cardiff, from Shrewsbury to Bala and from Chester

to Aberystwyth, all passed within fairly close proximity to Ann’s

home. Indeed, as Dr Roberts has remarked, the area was better

served by public transport in her day than now!

Ann’s native area, then, was no backwater, despite its

being rural. It was open to influences of all sorts, and the various

awakenings of the eighteenth century – economic, cultural,

political and religious – were all to affect Ann, her family

and her community in a variety of ways and to varying degrees.

|

Ann Griffiths Country

(Christine James) |

Ann’s family

Ann was born into a family that was fairly comfortable in financial

terms, a farming family prominent in the local community. Her

parents, John Evan Thomas and Jane Theodore, were both born in

the parish of Llanfihangel-yng-Ngwynfa. Her father’s family

roots were deep in that parish and her mother’s roots also

lay deep in northern Montgomeryshire. When they married in February

1767, John Evan Thomas took his bride to live at his parents'

farm, Tŷ Mawr Dolwar, and there their first two children were

born, Jane in 1767 and John in 1769. In 1770 the family moved

to Dolwar Fach, and it was there that their other three children

were born, Elizabeth in 1772, Ann in 1776 and Edward in 1779.

The Dolwar Fach family seems to have been close-knit and hospitable,

popular in the locality and prominent in the social and cultural

life of the community. John Evan Thomas is said to have been a

sensible, genial and diligent man, highly respected in the neighbourhood.

He could read and write, and served on a number of occasions as

Churchwarden and also as one of the parish’s Overseers of

the Poor, both of which were key offices in local community life

during that period. We know little of his wife, Jane Theodore,

apart from the fact that she was probably related to some of the

more well-to-do families of the neighbourhood.

Brothers and sisters

Ann’s elder brother, John, worked at home on the farm all

his life. He remained unmarried. He died about eighteenth months

after his sister Ann, and was buried in January 1807 in Llanfihangel

churchyard.

The other brother, Edward, worked at home on the farm until 1801.

He married in 1798 and brought his wife, Elizabeth Savage, to

live at Dolwar Fach. In the spring of 1801, Edward and Elizabeth

moved to their own small farm a few miles away in the parish of

Llangynyw, taking with them their young son, John, who was born

in October 1799 – and it is worth remembering that from

October 1799 until spring 1801 there was a baby boy at Dolwar

Fach, with his aunt Ann helping to rear him. Edward Thomas was

sentenced to a year’s imprisonment in 1819 after killing

another farmer during a quarrel. By then his family had moved

to the industrial valleys of south Wales, to the vicinity of Merthyr

Tydfil, where Edward Thomas died in 1852.

Ann’s elder sister, Jane, appears to have moved to the

market town of Llanfyllin, about five miles north-east of Dolwar

Fach, in 1791. She married a shopkeeper in that town named Thomas

Jones, who died in 1804, shortly after Ann’s marriage. Jane

then took responsibility for the business, transferring it in

turn to her only child, John (who was probably born around 1793).

Jane remarried in 1807. Her second husband, Abraham Jones (1775–1840),

was a prominent leader among the Calvinistic Methodists of Montgomeryshire.

Jane and Abraham Jones moved in 1830 to the Llanrhaeadr-ym-Mochnant

area, a few miles north of Llanfyllin, where she died in 1851.

Her son, John, was a prominent figure in Llanfyllin, and both

he and his son (another John) were in the forefront of the campaign

in the mid-nineteenth century to erect a monument to the memory

of his aunt, Ann Griffiths, in Llanfihangel-yng-Ngwynfa churchyard.

Elizabeth, Ann’s other sister, moved to the parish of Llangadfan

in 1793, on marrying Thomas Morris, a farmer from that parish.

She raised a fairly large family and died in 1818. Although Elizabeth

lived only about five miles to the south-west of Dolwar Fach,

there seems to have been a distinct coolness in her relationship

with the rest of her family, at least until her father’s

death in 1804.

Mistress of Dolwar

Both Ann’s sisters had left home before their mother’s

death in 1794, leaving Ann at 17 years of age as mistress of the

household; and she would remain mistress of Dolwar Fach for the

rest of her short life. As mistress of the household, she would

have been responsible for keeping house and supervising the work

of the maid (or maids). She, together with the maid(s), would

have been responsible for milking and for processing the milk,

butter and cheese, and would have helped with other chores around

the farm as necessity demanded. She would also have regularly

undertaken another important task, namely preparing and spinning

wool. Montgomeryshire was one of the main centres of the woollen

industry in Wales in that period. Many of the county’s farmers

spun wool in order to supplement their income, and at the time

of Ann’s death there was a loom, five spinning wheels and

about eighty sheep at Dolwar Fach.

Personal profile

Judging from the descriptions we have of Ann, we can gather that

she was taller than average and rather stately in appearance,

although gentle in character when one got to know her. She had

long dark hair, a high forehead and a slightly arched nose. She

was rather pale in complexion, with rosy cheeks and bright eyes.

We have no portrait of Ann. The familiar effigy of her in the

Ann Griffiths Memorial Chapel in Dolanog (reproduced on the home

page of this website) is an imaginary likeness based on descriptions

of her by contemporaries. Her nephew, John Jones of Llanfyllin,

apparently looked very like his aunt. A silhouette of him has

survived. It was reproduced, together with photographs of his

children and some other close relatives, in David Thomas’s

book, Ann Griffiths a’i Theulu [‘Ann Griffiths and

Her Family’] (1963), and between them we can gain a fair

idea of how Ann would have looked.

|

|

Silhouette of John Jones, Llanfyllin, and a picture of his daughter, Margaret

John Jones was a nephew of Ann Griffiths, and was apparently her living image |

Ann is described as being rather frail, no doubt reflecting the

fact that she was plagued by ill-health throughout her life. She

was often ill, and is said to have suffered from rheumatic fever

on three occasions during her lifetime. This was possibly the

cause of her death, since her heart may have been unable to stand

the strain of childbirth due to damage to the cardiac valves caused

by rheumatic fever. It is also possible that she was suffering

from tuberculosis at the time, and that that was another cause

of death. It is worth noting in passing that tuberculosis often

sharpens the sufferer’s faculties.

Although frail of body, Ann was strong in mind and character.

The picture we have is one of a young woman who was full of life,

rather impulsive, witty and mischievous by nature, single-minded,

meticulous and passionate. Ann is portrayed as being affectionate

and cheerful, and a born leader among her contemporaries. She

was a gifted person, with an astute mind and an exceptional memory,

and although she received little formal education, she was able

to both read and write. Ann was very much at home in the merry-making

which characterised the fairs and wakes and informal evening entertainment

of her day, and she was especially fond of dancing.

Religious upbringing

Ann received a religious upbringing. Her father was a conscientious

member of the Anglican Church, the established church in Wales

at that time, and he regularly attended the services at Llanfihangel

parish church. An indication of the regularity of Ann’s

father’s attendance at church over an extended period is

to be found in the story of an old sheepdog at Dolwar Fach. The

dog would follow his master to church every Sunday morning and

lie quietly under his pew until the service ended; indeed, it

is said that attending church had become such a habit for the

dog that he would go regularly every Sunday, even when no members

of the Dolwar family were present!

John Evan Thomas conducted family devotions at Dolwar Fach every

morning and evening, at which he would read parts of the Welsh

translation of the Book of Common Prayer. Consequently, from an

early age, Ann became familiar with the Welsh Bible and majestic

religious prose in Welsh, and their influence would be seen on

her hymns and letters in due course.

|

Llanfihangel-yng-Ngwynfa Parish Church

(Picture: John Thomas)

The present church was built in 1862-63.

The Ann Griffiths memorial column, erected in 1864, is on the right.

|

Carol and englyn

Despite its proximity to the English border, the community language

in Ann’s area was Welsh. Her district sported a lively cultural

life during Ann’s youth, especially as regards poetry. Poems

in traditional Welsh strict-metre forms, such as the englyn and

the cywydd, written in cynghanedd (an intricate system of alliteration

and assonance), were very popular, as were ballads and rustic

plays (or anterliwtiau as they were called, derived from the English

word ‘interlude’). Indeed, the chief exponent of such

plays, Twm o’r Nant (Thomas Edwards; 1739–1810), lived

in the area for a time when Ann was a small girl.

Carols were especially popular in the area, carolau haf (summer

carols) and carolau plygain in particular. The traditional Welsh

plygain carols were sermons in song, full of biblical phrases

and references, in complex metres. They were composed to be sung

at the early morning Christmas service (the Welsh word plygain

comes from the Latin for ‘cock crow’). Although they

refer to the birth of Christ, their main theme is to trace the

salvation in Christ from beginning to end, often starting in the

garden of Eden, and ending with exhortations to faith and repentance

and good works. This particular Christmas carol-singing tradition

was at its strongest in northern Montgomeryshire, and a form of

that tradition persists to this day in the area around Llanfihangel-yng-Ngwynfa.

Ann and her family were heavily involved in the bustling cultural

life of their community. According to her biographer, Morris Davies,

their neighbours would congregate in Dolwar Fach to hold informal

evening entertainment, or nosweithiau llawen (lit. ‘merry

evenings’), where there would be singing to harp accompaniment,

dancing, and playing cards and dice. Morris Davies also tells

how Ann’s father would sing carols while he and the family

were spinning and weaving wool. Her father belonged to a circle

of local poets which flourished under the leadership of the colourful

bardic teacher, Harri Parri (1709?–1800) of Craig-y-gath.

Some englynion by Ann’s father have survived, and it seems

that Ann herself could craft an englyn by the time she was about

ten years of age. In the Cwrt Mawr manuscript collection held

at the National Library of Wales there is a substantial volume

of poetry called ‘Llyfr Dolwar Fach’ [‘The Book

of Dolwar Fach’], which contains a mix of poems by both

local and better-known poets. The manuscript was for many years

the property of Harri Parri, Craig-y-gath, but it seems to have

passed into the possession of the Dolwar Fach family in 1796.

In that year Ann wrote her name and address on one of its pages,

and her hymns display the legacy of that bardic background –

in the touches of cynghanedd alliteration, in her sensibility

to linear balance, and in the paradoxes which pervade her work

and are reminiscent of the paradoxes which characterise the plygain

carols.

‘Ann the English’

Although Welsh was the community language in Ann’s locality,

this was a border area, an area open to cultural cross-fertilisation

of all kinds over the centuries. Socially and culturally the pull

was strongest westward, with many people following the paths over

the Berwyn mountains towards Bala and the Vale of Clwyd. To the

east, those same paths lead to Shropshire; and while socially

and culturally, there was a strong westward pull, economically

there was a strong eastward pull, towards the more prosperous

English lowlands. In one of her letters Ann uses an illustration

in which a shopkeeper goes to Chester to buy £200 worth

of goods to sell in his shop back home; and it is quite possible

that Ann would have gone to Chester, and to Shrewsbury perhaps,

not to mention Oswestry, with her sister Jane, who kept a shop

in Llanfyllin.

The case of a farm-worker called John Owen, who lived near Dolwar

Fach, emphasises the connections between Ann’s locality

and the English areas to the east. Like many others from the vicinity,

John Owen would go every year to work on the harvest in Shropshire.

He returned one year with a wife, Ann y Sais (‘Ann the English’)

as she was nicknamed by the people of Llanfihangel. It appears

that Ann Griffiths attended a school held by ‘Ann the English’

for a time, and it was there that she learned to read English

and to write. Although she never became fluent in English, it

is said that Ann Griffiths was able to compose light verse in

that language and to write the occasional English letter, although

no examples have survived. In this context, it is also interesting

to note D. Gwenallt Jones’s suggestion that English hymns

had some influence on her work.

‘Sam the English’ and Thomas Charles

Ann Owen, Ann y Sais, had a son called Samuel – or Sam y

Sais (‘Sam the English’) as he was known locally,

despite the fact that he was a fluent Welsh speaker. Sam was a

Methodist, and it was he who was responsible for introducing Methodism

to the Dolwar Fach household. This revolutionary evangelical movement

had begun in south Wales in the 1730s through the likes of Daniel

Rowland, Howel Harris and William Williams of Pantycelyn, but

by Ann Griffiths’s youth it was spreading increasingly in

north Wales, especially under the influence of the evangelical

clergyman, Thomas Charles (1755–1814), a native of Carmarthenshire

in south Wales who settled in the town of Bala, a strategically

central location in north Wales, in the mid-1780s.

From his power base in Bala, and especially through his evangelistic

and educational campaigns (his circulating schools initially,

followed by Sunday schools), Thomas Charles’s influence,

and the influence of Methodism, spread widely throughout north

Wales, with the result that north Wales would eventually become

as much of a stronghold for Methodism as south Wales, despite

that movement having its origins in the South. Although one could

argue that the advent of Methodism to Dolwar Fach was a result

of influences from the east, since it was ‘Sam the English’

who introduced Methodism to the family, one must look to the Welsh-speaking

west, and especially over the Berwyn mountains to Bala and to

Thomas Charles, to find the most important religious influences

on Ann Griffiths.

Calvinistic Methodism

Methodism was a movement which placed great emphasis not only

on the orthodox beliefs of the Christian faith, but on the personal

experience of those beliefs, on feeling the truths of the Faith.

To quote Ann Griffiths’s biographer, Morris Davies, it was

a religion of heat as well as light. Methodism was not a phenomenon

confined to Wales, of course. There was a strong Methodist movement

in eighteenth-century England also. However, it must be emphasized

that the relationship between Welsh and English Methodism was

one of sisters rather than of mother and daughter. Welsh Methodism

in the eighteenth century was an indigenous movement with its

own separate origins, and not an import from England; and whereas

eighteenth-century English Methodism divided into two main camps

(the Calvinistic Methodists, led by George Whitefield, and the

Arminian Methodists, led by John Wesley), eighteenth-century Welsh

Methodists were predominantly Calvinists.

Until 1811 Welsh Calvinistic Methodism was officially a movement

within the Established Church and not a separate denomination.

Nevertheless, the Welsh Methodists became increasingly denominational

in stance as the eighteenth century unfolded, developing their

own leadership, their own places of worship, and their own independent

connexional organisation. Members of the movement would meet together

in local groups called seiadau (singular seiat, from the English

word ‘society’), where they would discuss and examine

their religious experiences and receive help and instruction on

their spiritual journey. In addition, there was a network of monthly

meetings and quarterly association meetings (or sasiynau; singular

sasiwn) to superintend the work.

North and south Wales had separate Associations. Their quarterly

association meetings were peripatetic, but from around 1760 the

June meetings of the North Wales Association settled permanently

in Bala. These Bala Association meetings developed into a great

annual festival for the Methodists in the North, with thousands

flocking there to the public preaching meetings. Preaching had

a central role in the Methodist movement. In Ann Griffiths’s

day, an army of Methodist preachers roamed the length and breadth

of Wales, and public preaching meetings were an indispensable

feature of both the monthly meetings and the quarterly association

meetings.

The Pontrobert seiat

The concurrence of religious and cultural awakenings is a common

feature of Welsh history, and that was the case in Llanfihangel-yng-Ngwynfa

in the 1790s. As has already been mentioned, it was a period of

marked vitality as regards poetry, and it was also a period which

witnessed a powerful religious revival, with a significant number

of people in the area becoming Methodists.

|

| The Old Chapel, Pontrobert

(Illustration: R. Brian Higham) |

This powerful religious revival had a deep and

lasting effect on Ann and her family. One after another, almost

every member of her family joined the Methodists and became prominent

members of the local Methodist seiat. For a time, the

main meeting place for that seiat was in the vicinity

of Pen-llys; but as it grew, the seiat moved its main

centre a mile or two south to Pontrobert, a better populated and

more central location, where a Calvinistic Methodist chapel was

built in 1800. However, the seiat continued to meet in

other places, including Dolwar Fach. Dolwar Fach was officially

licensed as a place for public worship in the summer of 1803,

but it appears that the Calvinistic Methodists had been holding

meetings there from around 1798 onward, possibly from about the

time Ann’s father joined the Pontrobert seiat.

Persecution and ridicule

In the Llanfihangel-yng-Ngwynfa of Ann’s day, the Methodists

and their religion were frowned upon and ridiculed. The majority

of the population remained faithful to the Established Church

and regarded Dissenters, and especially Methodists, with contempt

and suspicion. Like many local poets during this period, Harri

Parri of Craig-y-gath was strongly opposed to Dissent and Methodism,

and attacked both in verse. Attacks were sometimes physical. For

example, blood could be seen trickling over the Bible of the Methodist

preacher, Edward Watkin of Llanidloes, after he was hit by a stone

while trying to preach in the open air in Llanfyllin one Sunday

afternoon in 1795. But the most common form of persecution was

mockery, and it appears that Ann was more than ready to use her

eloquence to ridicule the Methodists.

Like Harri Parri, the Dolwar Fach family were

at first strongly prejudiced against Dissent and Methodism; but

as has already been noted, in the space of a few years during

the 1790s almost every member of the family became Calvinistic

Methodists – first John, Ann’s brother, and then her

sister, Jane, followed by Edward, Ann herself, and their father,

John Evan Thomas. As a result, they turned their back on Llanfihangel

parish church, not to mention the leisure activities of the majority

of their fellow-parishioners and the entertainment which characterised

the fair, the patronal festival and the noson lawen.

In Dolwar Fach, then, at the end of the eighteenth century, two

religions and two cultures met and vied for supremacy, with evangelical

religion and its culture eventually winning the day. In that respect

Dolwar Fach may be considered a microcosm of the history of Wales

in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries.

Ann and the Methodists

Ann joined the local Methodist seiat in the wake of a

series of intense spiritual experiences which transformed her

life over a period of about a year, when she was between 20 and

21 years of age. A number of traditions exist as to how and when

Ann came to hear the Congregational minister, Benjamin Jones of

Pwllheli, preaching in Llanfyllin, but the most likely turn of

events is as follows. One of the main fairs in the Llanfyllin

calendar was that held on the Wednesday before Easter. However,

the merry-making connected with that fair continued over the whole

of the Easter period. On Easter Monday 1796, when Ann was almost

20 years of age, she went to Llanfyllin to join in the revelry.

Jenkin Lewis, the minister of the Congregational cause at Pen-dref

Chapel, Llanfyllin, had established a series of ‘Easter

Meetings’ in order to counteract the influence of the fair,

and in 1796, Benjamin Jones of Pwllheli was the guest preacher.

According to tradition, as Ann passed by an open-air preaching

meeting being held outside a tavern in the centre of the town,

the preacher’s words made a great impression.

|

Pen-dref Chapel, Llanfyllin

One of the oldest Nonconformist causes in Wales.

The present building was erected in 1829. |

After months of unease of conscience and concern

for her spiritual state, and after failing to find succour in

Llanfihangel parish church, Ann decided she would have to search

elsewhere for a solution to her spiritual crisis. Although her

two brothers, and a number of her contemporaries, had by then

gone through similar spiritual experiences and had joined the

local Methodist seiat at Pontrobert, Ann remained very

prejudiced against the Methodists. She began making plans to go

and live in Llanfyllin in order to attend the meetings of the

Congregationalists there; but before her plans came to fruition,

she ventured to Pontrobert to listen to a Methodist preacher and

gained such spiritual benefit from so doing that her prejudices

against the Methodists were dispelled. As a result she joined

the local Methodist seiat and would spend the rest of

her life as an active and committed member both of that seiat

and the wider Methodist movement. Consequently, she would often

journey over the Berwyn mountains to Bala, to attend the Calvinistic

Methodist preaching meetings there and to receive the Sacrament

from Thomas Charles.

Intense spiritual experiences

The immediate consequence of Ann’s attending Methodist meetings

was to intensify her consciousness of being far from God and unable

to meet his standards and, as a result, of being under his just

condemnation. Her friend and spiritual counsellor, John Hughes,

a young man from the same parish, who had become a member of the

local Methodist seiat shortly before Ann began attending,

could say: ‘She experienced strong convictions of her sinfulness

and her lost condition. The authority and the spirituality of

the law [i.e. the law of God] gripped her mind so powerfully that

she would sometimes roll on the ground on her way home from listening

to sermons at Pontrobert, in terror and tribulation of mind.’

She was not long in that condition, says John Hughes, before

coming to see through faith that Jesus Christ – the One

who was God and man in the same Person – had taken the punishment

for her sin upon himself through dying in her stead, thereby ensuring

for her forgiveness and eternal reconciliation with God. Even

as her lost condition had weighed so heavily upon her that she

would sometimes roll on the ground on the way home from preaching

meetings, now, after coming to an assurance of faith, she would

sometimes drink so deeply of the joy of salvation that she would

break out into periods of rejoicing, both publicly and in private,

with the sound of her praise in her room being audible some fields’

length from the house at Dolwar Fach.

Ann experienced conversion during a period of

general spiritual awakening in the seiat at Pontrobert.

However, Ann’s spiritual experiences during her conversion

were particularly intense, even for a time of religious awakening.

That intensity of spiritual experience during conversion was a

foretaste of the passion which was to characterise the whole of

her spiritual life. Intense spiritual experiences were not unfamiliar

to Thomas Charles of Bala and John Hughes, Pontrobert. Both were

very conversant in matters of the soul, and familiar with dealing

with people who had received deep spiritual experiences during

times of religious awakening. Furthermore, both had themselves

been the subject of deep spiritual experiences. Yet Ann’s

spiritual experiences made a great impression on even those two

proficient church leaders. For example, in 1840, when John Hughes,

Pontrobert was 65 years old, he could say of Ann Griffiths that

she was ‘a woman of stronger faculties than normal for the

female sex; she also shone with greater intensity and prominence

in spiritual religion than anyone I saw during my lifetime’.

It has already been observed that Llanfihangel-yng-Ngwynfa was

a border area and a cultural crossroads, and that Dolwar Fach

was a meeting place for two types of religion and two forms of

culture at a crucial period in Welsh history. In the light of

the exceptional spiritual experiences mentioned above, Canon Allchin

goes further and says that Dolwar Fach in Ann’s day was

a notable meeting place of time and eternity, of heaven and earth.

Ann Griffiths’s work

Ann, then, was considered a person whose spiritual experiences

were remarkable even at a time of powerful religious awakening.

The examples of Ann’s work that have been preserved for

us are both the fruit of those intense spiritual experiences and

an expression of them.

The sum total of her surviving work is small: eight letters and

just over 70 stanzas, and only one letter and one stanza in her

own hand. The two people who are central to the preservation of

her work are John Hughes, Pontrobert, and his wife, Ruth Evans.

|

John Hughes,

Pontrobert

(1775-1854) |

John Hughes (1775–1854) was a poor young

weaver from the same parish as Ann. He was a year older than her

and had become a member of the local Methodist seiat

a year prior to her. He would soon become a promising young leader

among the Calvinistic Methodists in Montgomeryshire and would

remain an influential preacher in their midst for more than fifty

years. He became a spiritual mentor and counsellor to Ann Griffiths

soon after her conversion, and his short memoir of Ann, published

in the periodical Y Traethodydd [‘The Essayist’]

in 1846, forty years after her death, is the single most important

source we have for her life and character.

Ruth Evans (1779?–1858) was a maidservant at Dolwar Fach.

She was from Llandrinio, a part of Montgomeryshire very close

to the English border. Her parents were among the pioneers of

the Methodist cause in that area and she herself became a Methodist

in about 1791. Ruth came to Dolwar Fach as a maidservant in May

1801 and remained there until her marriage to John Hughes in May

1805. A special friendship developed between her and Ann during

this period. John and Ruth Hughes lived in a number of locations

in the vicinity of Pontrobert during the early years of their

marriage, but by 1811 they had moved to the small house attached

to the Methodist chapel in Pontrobert, erected in 1800, where

they spent the remainder of their long lives.

Ann’s letters

Seven of the eight letters by Ann which have been preserved were

sent to John Hughes. The original letters have not survived; however,

John Hughes made copies of them in a copy-book soon after receiving

them, and that manuscript book is now held at the National Library

of Wales in Aberystwyth.

Shortly after joining the Methodists, John Hughes became a teacher

in Thomas Charles’s circulating schools. Towards the end

of 1799 or the beginning of 1800 he began to keep school in the

Llanfihangel-yng-Ngwynfa area, lodging at Dolwar Fach for some

months. While there, as John Hughes himself tells us, he would

spend ‘on many occasions several hours conversing with Ann

on scriptural and experiential matters, and that with such delight

that the hours would pass unawares’.

John Hughes left Dolwar Fach in 1800, and from then until the

spring of 1805, although he visited the Llanfihangel and Pontrobert

area quite regularly, he taught in circulating schools in south-west

Montgomeryshire, in the area between Machynlleth and Llanidloes.

It was during this period that the correspondence between him

and Ann arose, as a continuation of their conversations at Dolwar.

Ann’s first letter to John Hughes is dated 28 November

1800. All except one of the other six letters are undated. They

were all written before Ann married in October 1804, since they

are all signed ‘Ann Thomas’, and there is reason to

believe that they were all written between November 1800 and the

summer of 1802. Only one of John Hughes’s letters to Ann

has been preserved, and that is also undated; however five of

his letters to Ruth Evans during her time as a maidservant at

Dolwar Fach have survived. The five belong to the years 1803 and

1804. It is fairly certain that Ann would have read these letters

since they are not ‘private’ love letters but rather

letters on subjects of a spiritual nature. It would have been

quite normal for Ruth to share their content with others, and

there are a number of interesting concurrences between these letters

and Ann’s hymns as regards both content and actual wording.

Indeed, comparing Ann and John’s work leads one to agree

wholeheartedly with O. M. Edwards when he said: ‘In the

years 1800–1805, Ann Griffiths’s mind and John Hughes’s

mind were on the same matters.’

The only letter that has survived in Ann’s

own hand was sent to another young Methodist, a young woman named

Elizabeth Evans, who was a maidservant on a farm called Bwlch

Aeddan in the parish of Guilsfield, a few miles east of Dolwar

Fach. It is possible that this Elizabeth Evans was a sister of

Ruth Evans, the maidservant at Dolwar Fach and spiritual confidante

of Ann Griffiths. This letter is also undated. Since the date

1801 was at one time visible on a watermark on the paper on which

the letter was written, and since it is signed ‘Ann Thomas’,

we can date the letter to sometime between 1801 and October 1804,

and it is quite possible that it was written around the summer

of 1802. The original letter is one of the great treasures of

the National Library of Wales in Aberystwyth. Ann appended to

the letter the stanza ‘Er mai cwbwl groes i natur yw

fy llwybyr yn y byd . . .’ [‘Although my path

in the world is totally contrary to nature . . .’], the

only example of her poetry to survive in her own hand.

Seiat matters; seiat language

Although Ann’s letters have not been afforded as much attention

as her hymns, it is important to remember that such critics as

Saunders Lewis consider them to be spiritual classics, containing

examples of notable religious prose. The letters take us headlong

into the rarefied atmosphere of the Methodist seiadau

at the end of the eighteenth century and the beginning of the

nineteenth. There is a certain difference in aura between Ann’s

letter to Elizabeth Evans and those she wrote to John Hughes.

In the letter to Elizabeth Evans, Ann shares her experiences with

a ‘sister in the Lord’, whereas in those written to

John Hughes she is sharing them with a spiritual counsellor, one

who is her ‘father in the Lord’ despite there being

only a year’s difference in age between these two young

Methodists. Yet, in essence, the content of all the letters is

uniform. Scriptural verses, the spiritual state of the Pontrobert

seiat and of religion in general, and her own spiritual

condition in particular – ‘relating how things are

with me’ – that is Ann’s subject matter in each

and every letter. Essentially, then, the letters are discussions

on seiat matters by seiat members in seiat

language, and not informal letters between close friends.

The letters reveal warm relationships, as evidenced

by greetings such as ‘Dear sister’ and ‘Dear

brother’ which pepper them throughout; yet their whole stance

and diction betray them to be an extension of the formality and

courtesy of the seiat. Furthermore, it is important to

remember that these were not private letters, despite their being

poignantly personal at times as Ann proceeds to analyse her spiritual

condition. Such analysis was characteristic of the seiat,

and Ann would expect her fellow seiat-members to read

her remarks in these letters, just as she would expect them to

listen to her oral contributions in the seiat, and as

she in turn would read for her spiritual benefit the letters John

Hughes sent to her brother John, to Ruth and to other friends

at the Pontrobert seiat. Indeed, when John Hughes received

letters from Ann, it appears he would read them aloud in the local

seiat he attended wherever he happened to be schoolmaster

at the time, ‘for the edification and comfort of the members’.

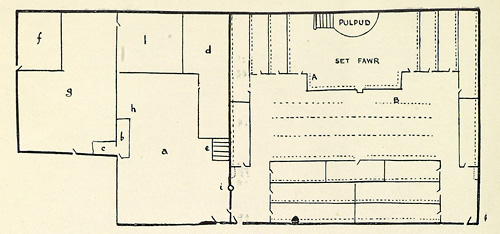

|

The plan of the chapel is on the right,

and the plan of the house and outbuildings is on the left.

The dotted lines represent benches.

A: John Hughes's place in the 'big seat' (sÍt fawr);

B: his place in the seiat.

a: John Hughes's kitchen; b: the fireplace; c: fireplace

oven; d: the pantry; e: the stairs to the loft; h: John

Hughes's chair in the corner near the fire; i: round hole

in the chapel wall, to enable those in the house to hear.

f: John Hughes's cowshed; g: the chapel's stable; l: stable

for the preachers' horses.

|

Floorplan of the Old Chapel, Pontrobert

(from Cymru 1906)

The chapel was erected in 1800 for the local

Calvinistic Methodist seiat.

Ann Griffiths would sit to the left of the pulpit.

The house which is attached to the chapel was the home of

John Hughes and Ruth Evans

for most of their married life. |

Ann’s hymns

It is quite likely, therefore, that Ann would not be over-troubled

by the knowledge that her letters are read and discussed by people

today. However, her hymns are a different matter altogether, for

to her the private compositions were not her letters, however

poignantly personal they can be at times, but rather her hymns,

despite their being in some ways much more objective in content.

We can probably justify referring to Ann Griffiths’s

poems as ‘hymns’ on the basis that they are praise

poems and that they are poems to be sung; but they are most certainly

not congregational hymns. It is clear that Ann was conscious

of the exceptional nature of her spiritual experiences, and that

she felt the need to record them. According to John Hughes, Pontrobert,

she had at one time intended to keep a religious journal. Instead

of that, he says, she began to compose verses of hymns when there

was ‘something in particular on her mind’; and several

anecdotes have been preserved which suggest that her hymns are

the product of periods of deep meditation – periods when

she would ‘completely fail to stand in the way of my duty

with regard to temporal things’, as she explains in her

letter to Elizabeth Evans. Her hymns, then, are a kind of personal

diary, recording and encapsulating her religious experiences and

perceptions.

It is true that a number of her stanzas became

the property of a wider circle during Ann’s own lifetime.

It appears that Methodist preachers who came to Dolwar Fach to

hold meetings were the means of spreading some of them to other

seiadau. Other verses were probably circulated in letters

to friends, like the one Ann appended to her letter to Elizabeth

Evans. Ann recited some to members of her family; she recited

many of them to Ruth the maid. But not all. It is clear that she

sometimes felt the need to keep some of her verses completely

to herself. It is said that on occasions she would hide verses

on pieces of paper under the cushion of the cane chair in the

kitchen, and that Ruth would take a stealthy look at them and

learn them; and when Ruth urged Ann, as her health deteriorated,

to record her verses on paper lest they be lost, her answer was

that she did not feel they were worthy of preservation. ‘I

do not wish anyone to have them after me,’ she said; ‘I

compose them for my own comfort.’

Fortunately, Ann did not have her way. Ruth’s memory, and

both her realization and that of others, of the hymns’ value,

prevailed. After Ann’s death, Ruth recited them to Thomas

Charles of Bala. Ruth could not write, but Thomas Charles urged

her husband, John Hughes, to write the hymns down so that he might

publish them. That is what happened, and a good number of the

stanzas were published in a small collection of hymns which appeared

within a few months of Ann’s death.

Publishing Ann’s work

John Hughes recorded Ann’s stanzas in copy-books which are

now held at the National Library of Wales. Around two-thirds of

those stanzas were published, together with the work of other

hymn-writers, in a slim volume entitled Casgliad o Hymnau

[‘A Collection of Hymns’], printed in Bala in early

1806. At around the same time, a number of these stanzas were

published in an appendix to the second edition of an influential

hymnal compiled by Robert Jones (1745–1829) of Rhos-lan,

Grawn-sypiau Canaan [‘Bunches of Grapes from Canaan’],

and it is quite possible that Robert Jones assisted Thomas Charles

in preparing Ann’s hymns for publication.

There are significant differences between Ann

Griffiths’s stanzas in Casgliad o Hymnau (1806)

and the form in which they appear in John Hughes’s copy-books,

not only with regard to their wording but also in the way they

are combined into hymns. It is now generally accepted that their

form in John Hughes’s copy-books, rather than that in Casgliad

o Hymnau (1806), is usually closest to the original form

of composition, and that many of the differences between John

Hughes’s manuscript versions and the early printed versions

are the result of editorial interference by Robert Jones and Thomas

Charles (and possibly John Hughes).

Of those stanzas in John Hughes’s copy-books

which were not published in Casgliad o Hymnau (1806),

John Hughes published all but seven when he published Ann’s

biography in the middle of the nineteenth century, revising them

at will rather than reproducing them in the form in which they

were recorded in his copy-books. Of the remaining seven unpublished

stanzas, five were not published until 1882, and the final two

did not appear in print until 1903.

Although Ann’s stanzas were republished

regularly during the nineteenth century, and were selected for

inclusion in numerous nineteenth-century hymnals, it is important

to note that it was the edited versions produced by Thomas Charles,

John Hughes and Robert Jones, Rhos-lan, which were in circulation

throughout that century. It was not until 1905 that John Hughes’s

manuscript versions were published for the first time, in the

volume Gwaith Ann Griffiths [‘The Work of Ann Griffiths’],

edited by O. M. Edwards. It is worth remembering, therefore, that

Ann Griffiths’s growing reputation during the nineteenth

century was founded on texts of her hymns which were at times

very different from their original form.

This is also true of Ann’s letters. John Hughes published

three of these for the first time in periodicals during the years

1819–23. The remaining five appeared for the first time

with his biography of Ann Griffiths in 1846. Yet again, John Hughes

was quite prepared to edit and revise the letters rather than

faithfully reproduce the manuscript versions, and it was the beginning

of the twentieth century before the letters appeared in print

in the form in which they are preserved in John Hughes’s

manuscripts.

Order and date

There are 73 stanzas which may be ascribed to Ann with some confidence.

They form 30 hymns. Some of these hymns comprise a single verse,

while the longest, her magnificent poem ‘Rhyfedd, rhyfedd

gan angylion . . .’ [‘Wondrous, wondrous to angels

. . .’], is a notable composition in seven verses. Her single-verse

hymns are often less well-crafted than the multi-verse ones, and

it is possible that a number of them are fragments of poems which

have not been fully developed. The multi-verse hymns often give

the impression of having started out as single verses, the product

of short periods of intense meditation, which then developed into

longer compositions, step by step, over a period of months or

even years. Did Ann herself combine the individual verses into

multi-verse hymns, or did John and Ruth, and others, play their

part? It is by now almost impossible to tell.

Although one can give tentative suggestions regarding the date

of composition of a few stanzas, it is impossible to state with

any confidence when and in what order they were composed. However,

one may cautiously suggest that the majority, if not all, of Ann’s

stanzas are the product of the period 1802–1804.

Metre

Ann employed a variety of metres in her stanzas, some eight in

all. However, the vast majority of her stanzas – some two-thirds

– are in the metre known as ‘87.87.Double’ (eight-line

verses, with alternate lines in eight and seven syllables). This

is an exceptionally popular metre in the history of Welsh hymnody.

It is a majestic metre whose eight long lines allow the hymnist

to compose on a wide canvas as regards both content and craft.

Almost all of Ann’s ‘87.87.Double’

verses are on a variant of that metre which allows for an irregular

number of syllables – the so-called ‘87.87.Dwbl

Clonciog’ [‘Jolting 87.87.Double’]. This

variant is characterised by the irregular inclusion of additional

unaccented syllables at the beginning of lines. It should be added

that irregular syllabic patterns are also characteristic of Ann’s

use of other metres. Her lines are regular in the number of accented

syllables, but not always in the total number of syllables.

This ‘metrical fault’ has been the

focus of much criticism over the years, and the cause of considerable

revision of her work by editors of hymnals keen to regularise

the length of her lines to facilitate congregational singing.

However, this characteristic of her work is not a metrical fault

as such. Syllabic irregularity was a common feature of Welsh folk-songs

in Ann’s day. There is no difficulty in singing Ann’s

so-called ‘jolting’ hymns on folk-tunes such as ‘Y

Ferch o Blwyf Penderyn’ [‘The Lass from Penderyn

Parish’], for example. All this serves to strongly suggest

that Ann had the popular folk-tunes of her locality in mind when

she composed a number of her hymns.

Characteristics of her hymns

This is not the place to elaborate on the characteristics of Ann’s

hymns. However, their chief characteristics may be summarised

under three headings:

1. Objective

As Saunders Lewis emphasised in his celebrated lecture, ‘Ann

Griffiths: Arolwg Llenyddol’ [‘Ann Griffiths:

A Literary Overview’], Ann is a poet of contemplation, a

poet of the intellect, a poet who gazes outwards in wonder at

the panorama of biblical truth. Her ability to think lucidly and

to give crystal-clear expression to that thinking, is one of the

most exceptional characteristics of her work. One striking feature

of her letters is the number of times the word meddwl

[‘mind’] occurs in them. Another important word in

her vocabulary is gwrthrych [‘object’], together

with words such as gweld [‘see’] and edrych

[‘look’]. ‘Behold standing among the myrtles

an object worthy of my desire’ she says in the opening lines

of one of her most famous hymns.

2. Subjective

In addition to the objective, a deep sense of personal experience

permeates her hymns. Her purpose in composing them was, in one

respect, to give expression to her spiritual experiences in order

to take fuller possession of them. The first person singular is

very prominent throughout her hymns. ‘An object worthy of

my desire’ is the One she sees standing among the

myrtles. Interestingly, two versions of that well-known verse

are preserved in different places in John Hughes’s copy-books.

Ann herself is probably responsible for the variations between

the versions; and together they serve to underline the blending

of the objective and subjective which is to be found throughout

Ann’s work, since the opening words of one version are ‘Wele’n

sefyll . . .’ [‘Behold standing . . .’],

emphasising the objective gaze, whereas the other opens with the

more subjective ‘Gwela’i yn sefyll . . .’

[‘I see standing . . .’].

3. Biblical

The Bible is central to Ann’s life and work. A very real

danger for one who received such powerful spiritual ‘visitations’

as Ann, would be to become controlled by those feelings and experiences.

Not Ann. To her, the Bible is God’s infallible Word, the

divine revelation which is the ultimate authority for every aspect

of her life, mind and experience. She feared ‘imaginations

of all sorts’, and gave thanks for ‘the Word in its

unconquerable authority’. Furthermore, the Bible plays a

key role in the process of forming and interpreting Ann’s

experience of God.

In the light of Ann’s high view of the Bible, it is not

surprising that the Scriptures were her chief reading material

and focus of her meditation. Phrases such as ‘that word

on my mind’ are a regular refrain throughout her letters,

as verse after verse from the Bible grips her mind and addresses

her condition. She immersed herself in the Bible, in all its parts,

both Old Testament and New. She saw it as one rich tapestry worked

by one divine Author. She also saw the whole as turning around

the person of Jesus Christ. He is the key to every part of the

Bible; to Him it all refers, sometimes overtly, sometimes in parable

and type.

Bearing all this in mind, it is not surprising that Ann’s

work is shot through with biblical references and resonances,

taken from all parts of Scripture. In respect of her use of biblical

references, it is appropriate to regard Ann Griffiths a classical

poet, for in her work the mind darts to and fro between the poem

and the source of the reference, each context enriching the other

in turn. Indeed, if we fail to consider Ann’s work in biblical

light, we not only lose strata of meaning and significance, but

we are also are in danger of seriously misunderstanding and misinterpreting

her work. For example, depths of meaning are lost unless we realise

that the line ‘Behold standing among the myrtles’

refers to the vision in the first chapter of the prophecy of Zechariah

in the Old Testament, and that Ann is interpreting that vision

of a mighty, armed warrior on horseback standing among the myrtles

in the hollow, as a portrayal of Christ defending God’s

people (the ‘myrtles’) in their low and straitened

circumstances.

All Welsh hymn-writers echo the Bible in their work, but Ann’s

use of the Bible is more concentrated than the others. The resonances

are more frequent and more tightly woven together. Derec Llwyd

Morgan has aptly described Ann as creating a collage of biblical

images in her work. Directly or indirectly, the language of all

her hymns is based on that of the Bible, and the Bible is the

source of all the imagery she employs in making concrete her ideas

and experiences. This has led to the accusation that Ann does

little more in her work than string biblical texts together. However

such comments are misguided, for it is clear that Ann selects

her imagery skilfully and creatively, and that she is so steeped

in the language of the Bible that she is able to make it the language

of her own deepest experiences.

Themes of her hymns

Nor is this the place to elaborate on the themes of Ann Griffiths’s

hymns. However their chief characteristics may also be summarised

under three heads:

1. Law

God’s law occupies a central place in the life and work

of Ann Griffiths. To her, in a sense, the law defines God’s

character, and draws together the various threads in the process

of salvation. The first thing the law does is show Ann that she

cannot fulfil its demands, that she has transgressed against God’s

law and that she is consequently unacceptable to him – in

a word, that she is a sinner. But the law also has a positive

role to play, for although it condemns her on the one hand, yet,

because it is an expression of God’s character and will,

it presents her with a pattern to emulate, it defines holiness.

2. Image

Running through Ann’s work is a deep desire for holiness,

a longing to conform with the pure and holy laws of heaven, and

to be found in the image of Christ. Although she strives towards

that in this earthly life, Ann is conscious that she will not

attain it completely this side of the grave. That goes part way

to explain the great longing for heaven expressed in her work.

Death will be gain for her, as she says in her letter to Elizabeth

Evans, since she will thereby ‘be able to leave behind every

inclination that goes against the will of God, to leave behind

every ability to dishonour the law of God, every weakness being

swallowed up by strength, to become fully conformed to the law,

which is already on our heart, and to enjoy God’s image

for ever’.

3. God-man

Yet it is not so much a longing for heaven which she expresses

in her work as a longing for Jesus Christ, for ‘the great

object of His Person’. In essence, the longing which pervades

her work is the desire to be in an unsullied and never-ending

communion with Christ: ‘Kissing the Son for eternity without

turning from Him ever again.’ He is the perfect pattern,

the worthy object. He is the only one, through his propitiatory

death on the cross, who is able to open ‘a lawful way for

lawbreakers to peace and favour with God’. He – who

is at once God and man, who encompasses and conciliates heaven

and earth – is the chief cause of the wonder which is such

an obvious characteristic in her work, and the chief source of

the paradoxes which are such an integral part of the warp and

weave of her thought and expression.

The final years

The years 1804 and 1805 saw great changes at Dolwar Fach. In February

1804 Ann’s father died suddenly. That was a bitter blow

which left its mark on Ann’s health for the rest of her

days. His death must also have added considerably to the workload

of both Ann and her brother John as they now shouldered the responsibility

of running the farm. In October 1804 Ann married Thomas Griffiths,

a young Methodist leader from a well-to-do family in the next

parish, but whose physical health was no better than that of Ann

and her brother John.

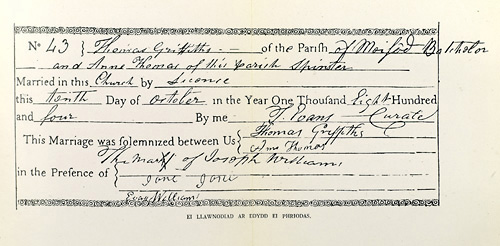

|

Record of the marriage of Thomas and Ann Griffiths in the

Llanfihangel-yng-Ngwyfa parish register |

In May 1805, Ruth Evans left Dolwar Fach when she married John

Hughes. Ann was some seven months pregnant at the time. When she

was born on 13 July 1805, Elizabeth, the daughter of Ann and Thomas

Griffiths, was a very weakly baby. She was baptized that same

day, not in Llanfihangel church, but by Jenkin Lewis, the minister

of Pen-dref Congregational Chapel in Llanfyllin. The child died

within a fortnight and was buried in Llanfihangel churchyard on

31 July 1805.

Ann herself was extremely weak after giving birth, and died less

than a fortnight after her daughter. She was buried on 12 August

1805, aged 29, in Llanfihangel churchyard. The following Sunday

John Hughes delivered a funeral sermon in her memory in the Methodist

chapel at Pontrobert. He chose as his text a verse from the first

chapter of Paul’s Letter to the Philippians – a verse

which commands a central place in Ann’s letter to Elizabeth

Evans, the only letter that has survived in her own hand –

‘For me to live is Christ, and to die is gain.’